A Letter from the PurseBop Editor

By Maura Carlin

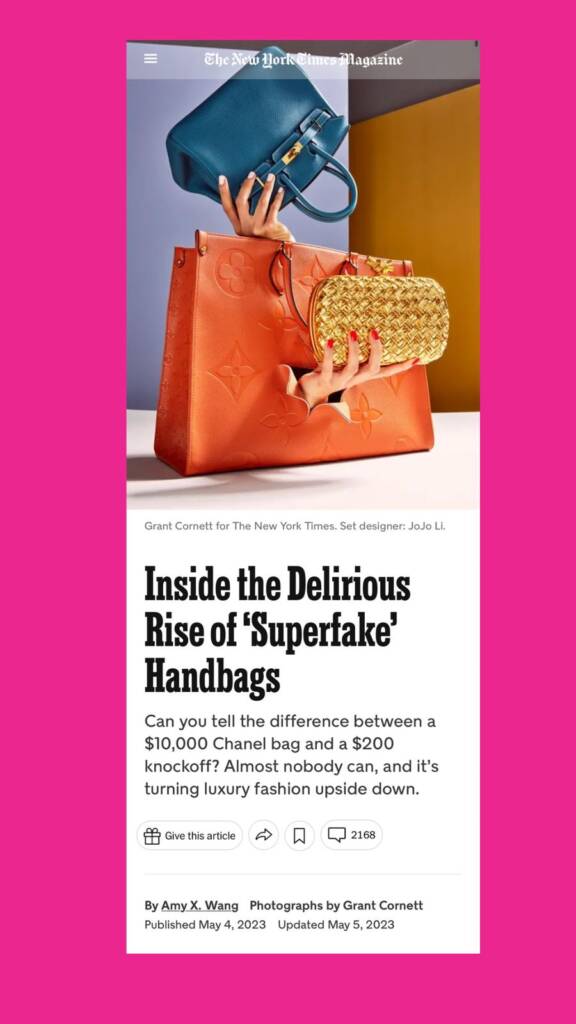

Last month’s New York Times exploration into the world of counterfeit luxury handbags – and particularly the more recent IG reel – had the PurseBop team scratching our collective heads. Is the NYT really promoting fakes, as some commenters argue? Or is this journalism, describing the experience and providing just the facts of purchasing on this not-so-secret market?

As PurseBop readers are no doubt well-aware, this is largely an anti-fake community. We consistently publish about the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) seizing fraudulent luxury products, sent from abroad to U.S. addresses, presumably for distribution here. Along with that we provide links to CBP statements about the dangers of counterfeit products and the economic damage. In most cases, it is theft of intellectual property. Further these products border on and often cross that fine line into fraud – selling fake goods as authentic.

To be sure, there have always been fake goods masquerading as the real thing. One need only think of New York City’s famed Canal Street. Or vendors selling wares on city streets. In those cases, the buyers know or should know that whatever the designer item purchased, it is not legitimately from the purported brand. If you’re paying $35 for a bag resembling Chanel’s $10,000 model, you know it’s not legitimate.

But what about those that try to pass off the fake as real? The street vendor bag may (or may not) be easily identifiable as a dupe. However, as discussed in the New York Times article it’s getting more difficult for even the well-trained to tell. So-called “superfakes” are faking everyone. Even the experts.

This problem multiplies as the secondary market continues to boom and luxury retail prices soar. Whether unable or unwilling to pay, many turn to resellers to save money. Paying $10,000 for a Chanel Classic Flap might be out of reach, but perhaps $5000 for a used bag is manageable. That is, as long as the pre-owned bag is in fact Chanel.

Which brings us back to that article and IG reel. Lest you think “who cares” about handbags, real or fake – think again. With over three million views and thousands of comments, a lot of people have a lot to say about what is probably the world’s most popular luxury accessory.

Amy X. Wang delineates her experience purchasing through a replica seller named “Linda” who sources the bags from factories in Guangzhou, China. She refers to published articles discussing “replicas” and wealthy women forgoing the real thing for fakes despite adequate means to afford the original. Wang seemingly questions why she (and others) want these high end expensive luxury bags while at the same time implicitly acknowledging that she does. But carrying the fake gave even more of a thrill.

She writes:

“There is a smug superiority that comes with luxury bags — that’s sort of the point — but to my surprise, I found that this was even more the case with superfakes. Paradoxically, while there’s nothing more quotidian than a fake bag that comes out of a makeshift factory of nameless laborers studying how to replicate someone else’s idea, in another sense, there’s nothing more original.”

And then there’s the IG reel, of Wang again discussing superfakes. Paying a fraction of the price (she describes a $2000 style for which she paid $100) and, despite comparing it to the real one at Celine, she could not tell the difference. She describes how the replica business from Guangzhou is set up in “blocks” so that if one piece of the chain is shut down, there are other sources to tap. That “authenticators” admit to the difficulty in identifying superfakes from the real thing.

However, she goes further, in what could be read as an invitation or encouragement to purchase fakes. Specifically,

“the entire process of buying a superfake bag myself, exposed me to how anticlimactic the real things are.”

Is this another way of saying – why buy real when superfakes are so good? Purchasing a superfake is not the same as opting for store brand toothpaste over Crest or Colgate. Nor is it akin to purchasing a quilted flap handbag “inspired by” Chanel’s hallmark style. Read: Is Every Quilted Flap a Chanel Copy?

There are laws and superfakes break them.

Yet, neither the article nor reel consider that the superfake industry is essentially a criminal enterprise. By the description, its shadowy structure of independent manufacturing and marketing blocks are intentionally designed to evade the authorities that they know want to shut it down.

The writer omits the potential dangers of purchasing counterfeit bags. It doesn’t consider who is working in the factories under what conditions – which fairly could be said about many industries and business. There’s also the concern about these enterprises funding terrorism and criminal enterprise, similarly ignored in the article.

At its core, the superfake industry engages in the theft of intellectual property. Brands invest in development and protection of designs and rights. As commenter @nikkihannaa aptly stated:

We see value in creators and creations. Even when they are big businesses run by the wealthiest men in the world. Or when they win lawsuits against artists that claim first amendment rights. That’s why there are laws protecting intellectual property – trademark, copyright, patents – applicable to, yes, handbags.

Enforcing these laws comes at a cost – to all of us. One has to assume that the expense of protecting intellectual property rights trickles down to buyers in the form of higher prices. In other words, the buyers of superfakes may be subsidized by the rest of us.

And there are the government resources worldwide expended on fighting fakes. CBP routinely checks shipments to the United States, seizing the counterfeit items to keep them out of circulation. All paid for by us, U.S. taxpayers.

A recent CBP exhibit at the Atlanta airport explained to travelers the risks of buying fake goods . . . and of carrying them wherever purchased. No the CBP officers aren’t just admiring your luxury handbags; they’re trying to discern whether it’s legit. If not, they will confiscate it.

The problem is not just American. There are signs at Paris’s Charles de Gaulle airport warning that carrying a fake bag is a crime subject to a €300,000 fine and up to three years imprisonment. Similar signs were spotted at Rome’s airport as well.

It is reasonable to question whether anyone should prioritize spending on luxury handbags. Challenging consumerism and influencer lifestyle, also are fair game. Think $10,000 is absurd when a free plastic bag or 99 cent tote would do? We get it; there’s plenty to debate. Of course, no one is making anyone purchase these bags. Don’t want it? Don’t buy it. And if you require the supposed prestige, status, or style of a designer product, well, that’s on you. No one “needs” to sport a bag purporting to be Hermès, Chanel, Gucci, or any other.

But here’s where we think the New York Times went too far. Its “news” piece pivots from reporting on the luxury bag industry and the superfake market to how the writer felt about it. That is where it teeters on advocating for buying fakes – the greater “smug superiority” of carrying a fake and the anticlimactic purchase of legitimate bags.

Yet, it is illegal, even if you get a thrill. You might like driving 100 mph on a 30 mph country road, but it’s against the law and dangerous, with consequences. The same is true for the superfake industry.

What are your thoughts on the New York Times article and IG reel?

xo,

PurseBop

Updated: June 14th, 2023

Comments

3 Responses to “A Response to the NYT Article on the Superfake Handbag Industry”

Dear PurseBop, I don’t know why we should be surprised by the NYT reporting on their support of fake bags; after all, they are at the top of the food chain for fake news.

Some had to say it

I bought a super fake/replica bag just to see what it was like. I like it and the bag does what it supposed to. I like for the style and design. Also I have a two inspired bags as well that are my favorite bags as well. On the hand I think the reason some people want to buy super fakes/inspired is so they don’t have to use their real ones that they paid so much money for and get them all dirty, tore up or stolen and so with that being said it depends on what type of bag the woman want to carry that is not for us to say.